Which Period Resulted In The Production Of Realistic Anatomical Drawings?

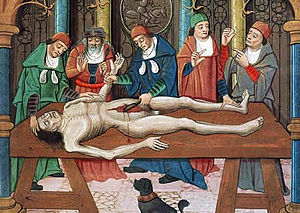

Dissection of a cadaver, 15th-century painting

The history of anatomy extends from the earliest examinations of sacrificial victims to the sophisticated analyses of the body performed by modernistic anatomists and scientists. Written descriptions of human organs and parts can be traced back thousands of years to aboriginal Egyptian papyri, where attention to the body was necessitated by their highly elaborate burying practices.

Theoretical considerations of the structure and function of the homo body did not develop until far later, in Ancient Greece. Ancient Greek philosophers, like Alcmaeon and Empedocles, and ancient Greek doctors, like Hipprocrates and his schoolhouse, paid attention to the causes of life, illness, and dissimilar functions of the body. Aristotle advocated dissection of animals every bit part of his program for understanding the causes of biological forms. During the Hellenistic Age, autopsy and vivesection of homo beings took place for the start time in the work of Herophilos and Erasistratus. Anatomical knowledge in antiquity would reach its noon in the person of Galen, who made of import discoveries through his medical practise and his dissections of monkeys, oxen, and other animals.

The development of the written report of anatomy gradually built upon concepts that were nowadays in Galen's piece of work, which was a part of the traditional medical curriculum in the Middle Ages.[1] The Renaissance brought a reconsideration of classical medical texts, and anatomical dissections became once once more fashionable for the first time since Galen. Important anatomical work was carried out by Mondino de Luzzi, Berengario da Carpi, and Jacques Dubois, culminating in Andreas Vesalius'south seminal piece of work De Humani Corporis Fabrica (1543). An understanding of the structures and functions of organs in the body has been an integral part of medical exercise and a source for scientific investigations ever since.

Aboriginal Anatomy [edit]

Egypt [edit]

The study of anatomy begins at least every bit early as 1600 BC, the date of the Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus. This treatise shows that the eye, its vessels, liver, spleen, kidneys, hypothalamus, uterus and bladder were recognized, and that the blood vessels were known to emanate from the heart. Other vessels are described, some carrying air, some fungus, and two to the correct ear are said to acquit the "breath of life",[ clarification needed ] while two to the left ear the "breath of death".[ citation needed ]The Ebers Papyrus (c. 1550 BC) features a treatise on the heart. It notes that the heart is the centre of blood supply, and fastened to it are vessels for every member of the body. The Egyptians seem to take known little about the office of the kidneys and the encephalon and made the heart the meeting point of a number of vessels which carried all the fluids of the body – claret, tears, urine and semen. However, they did not take a theory as to where saliva and sweat came from.[ii]

Ancient Hellenic republic [edit]

Much of the classification, methods, and applications for the report of anatomy tin can be traced back to the works of the ancient Greeks.[3] In the fifth-century BCE, the philosopher Alcmaeon may take been one of the first to have dissected animals for anatomical purposes, and possibly identified the optic nerves and Eustachian tubes.[iv] Ancient physicians such equally Acron, Pausanias, and Philistion of Locri may had also conducted anatomical investigations. Another important philosopher at the time was Empedocles, who viewed blood as the innate heat and argued that the center was the chief organ of the body and the source of pneuma (this could refer to either jiff or soul), which was distributed by the blood vessels.[5]

Many medical texts past various authors are collected in the Hippocratic Corpus, none of which can definitely exist ascribed to Hippocrates himself. The texts show an agreement of musculoskeletal structure, and the ancestry of understanding of the function of certain organs, such as the kidneys. The tricuspid valve of the heart and its function is documented in the treatise On the Heart.[ citation needed ]

The philosopher Aristotle (quaternary century BCE), alongside some of his contemporaries, labored to produce a system that made room for empirical inquiry. Through his work with animal dissections and biology, Aristotle engaged in comparative anatomy. Around this fourth dimension, Praxagoras may have been the commencement to place the difference betwixt arteries and veins, with more accurate descriptions of organs than in previous works.[ citation needed ]

In the Hellenistic period, the first recorded school of beefcake was formed in Alexandria from the belatedly 4th century to the 2nd century BCE.[6] Beginning with Ptolemy I Soter, medical officials were allowed to cut open up and examine cadavers for the purposes of learning how man bodies operated. The starting time use of human bodies for anatomical research occurred in the piece of work of Herophilos and Erasistratus, who gained permission to perform live dissections, or vivisection, on condemned criminals in Alexandria under the auspices of the Ptolemaic dynasty. Herophilos in particular developed a body of anatomical knowledge much more informed by the actual structure of the human trunk than previous works had been. He likewise reversed the longstanding notion made by Aristotle that the heart was the "seat of intelligence", arguing for the encephalon instead.[7] He also wrote on the distinction between veins and arteries, and made many other accurate observations well-nigh the structure of the human body, peculiarly the nervous system.[8]

Galen [edit]

The final major anatomist of aboriginal times was Galen, agile in the 2d century CE.[6] He was born in the ancient Greek urban center of Pergamon (now in Turkey), the son of a successful architect who gave him a liberal education. Galen was instructed in all major philosophical schools (Platonism, Aristotelianism, Stoicism and Epicureanism) until his father, moved by a dream of Asclepius, decided he should written report medicine. After his begetter's expiry, Galen traveled widely searching for the best doctors in Smyrna, Corinth, and finally Alexandria.[9] [ten]

Galen compiled much of the knowledge obtained by his predecessors, and furthered the inquiry into the part of organs past performing dissections and vivisections on Barbary apes, oxen, pigs, and other animals. Due to a lack of readily available human being specimens, discoveries through creature dissection were broadly applied to man anatomy likewise. In 158 CE, Galen served as chief physician to the gladiators in his native Pergamon. Through his position with the gladiators, Galen was able to report all kinds of wounds without performing any actual man dissection. Galen was able to view much of the abdominal crenel. His report on pigs and apes, notwithstanding, gave him more than detailed information about the organs and provided the basis for his medical works. Around 100 of these works survive—the most for whatsoever ancient Greek author—and fill 22 volumes of mod text.

Beefcake was a prominent part of Galen'due south medical education and was a major source of interest throughout his life. He wrote two peachy anatomical works, On anatomical process and On the uses of the parts of the torso of man.[eleven] The data in these tracts became the foundation of authority for all medical writers and physicians for the adjacent 1300 years until they were challenged past Vesalius and Harvey in the 16th century.[12] [13]

It was through his experiments that Galen was able to overturn many long-held behavior, such equally the theory that the arteries contained air which carried it to all parts of the body from the heart and the lungs. This belief was based originally on the arteries of dead animals, which appeared to be empty. Galen was able to demonstrate that living arteries comprise claret, but his error, which became the established medical orthodoxy for centuries, was to assume that the blood goes dorsum and forth from the heart in an ebb-and-period motion.[xiv] Galen also made the mistake of assuming that the circulatory system was entirely open up-concluded.[xv] Galen believed that all blood was absorbed by the trunk and had to be regenerated via the liver using food and h2o.[xvi] Galen viewed the cardiovascular system as a machine in which blood acts every bit fuel rather than a system that constantly recirculates.[17]

Although Galen correctly identified some of the organs involved in the vascular organization, many of their functions were not correctly established. Galen believed that the liver played a vital office in the circulatory system by creating all nutritious blood in the body. The eye, co-ordinate to Galen, kept the trunk warm and mixed the two types of blood via pores in the wall of the heart that separates the left and right ventricles.[xvi] Galen proposed that the heart's warmth allowed the lungs to expand and inhale air.[16] In contrast, Galen viewed the lungs equally a cooling region in the torso that also worked to expel sooty waste products from the lungs as they contract. In addition, Galen believed that the lungs kept the middle functioning properly past reducing the corporeality of blood in the right atrium, for if the right atrium contains too much blood, the pores in the heart do not dilate properly.[16]

Medieval to Early Modern Beefcake [edit]

Throughout the Middle Ages, human anatomy was mainly learned through books and animal dissection.[18] While it was claimed by 19th century polemicists that dissection became restricted after Boniface VIII passed a papal bull that forbade the dismemberment and humid of corpses for funerary purposes and this is still repeated in some generalist works, this claim has been debunked equally a myth past modern historians of science.[19]

For many decades human autopsy was thought unnecessary when all the knowledge about a human being trunk could exist read nearly from early authors such equally Galen.[20] In the twelfth century, as universities were being established in Italy, Emperor Frederick II made it mandatory for students of medicine to have courses on homo anatomy and surgery.[21] Students who had the opportunity to spotter Vesalius in dissection at times had the opportunity to collaborate with the animal corpse. At the risk of letting their eagerness to participate become a distraction to their professors, medical students preferred this interactive teaching style at the time.[22] In the universities the lectern would sit elevated before the audience and instruct someone else in the dissection of the body, but in his early years Mondino de Luzzi performed the dissection himself making him i of the kickoff and few to use a hands on approach to teaching human anatomy.[23] Specifically in 1315, Mondino de' Liuzzi is credited with having "performed the offset human being autopsy recorded for Western Europe."[24]

Mondino de Luzzi "Mundinus" was built-in around 1276 and died in 1326; from 1314 to 1324 he presented many lectures on human being anatomy at Bologna university.[25] Mondino de'Luzzi put together a book called "Anathomia" in 1316 that consisted of detailed dissections that he had performed, this book was used equally a text book in universities for 250 years.[26] "Mundinus" carried out the first systematic human dissections since Herophilus of Chalcedon and Erasistratus of Ceos 1500 years earlier.[27] [28] The first major evolution in anatomy in Christian Europe since the fall of Rome occurred at Bologna, where anatomists dissected cadavers and contributed to the accurate clarification of organs and the identification of their functions. Following de Liuzzi's early studies, 15th century anatomists included Alessandro Achillini and Antonio Benivieni.[27] [29]

Leonardo da Vinci [edit]

Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) was trained in beefcake by Andrea del Verrocchio. In 1489 Leonardo began a series of anatomical drawings depicting the platonic human class. This work was carried out intermittently for over 2 decades. During this time he made use of his anatomical noesis in his artwork, making many sketches of skeletal structures, muscles, and organs of humans and other vertebrates that he dissected.[30] [31]

Initially adopting an Aristotlean understanding of anatomy, he subsequently studied Galen and adopted a more than empirical approach, eventually abandoning Galen birthday and relying entirely on his ain direct observation.[32] His surviving 750 drawings represent groundbreaking studies in anatomy. Leonardo dissected around xxx human specimens until he was forced to stop under order of Pope Leo X.[ citation needed ]

Every bit an creative person-anatomist, Leonardo made many important discoveries, and had intended to publish a comprehensive treatise on human anatomy.[32] For case, he produced the commencement accurate delineation of the human spine, while his notes documenting his dissection of the Florentine centenarian contain the earliest known clarification of cirrhosis of the liver and arteriosclerosis.[32] [33] He was the first to develop drawing techniques in anatomy to convey information using cross-sections and multiple angles, although centuries would laissez passer before anatomical drawings became accepted as crucial for learning beefcake.[34]

None of Leonardo'southward Notebooks were published during his lifetime, many being lost after his death, with the effect that his anatomical discoveries remained unknown until they were later institute and published centuries subsequently his expiry.[35]

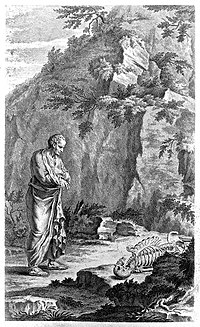

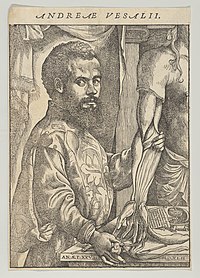

Vesalius [edit]

The Galenic doctrine in Europe was first seriously challenged in the 16th century. Thanks to the printing press, all over Europe a collective try proceeded to circulate the works of Galen and later publish criticisms on their works. Andreas Vesalius, born and educated in Belgium, contributed the about to human anatomy. Vesalius'due south success was due in large part to him exercising the skills of mindful dissections for the sake of agreement anatomy, much to the tune of Galen's "anatomy projection" instead of focusing on the work of other scholars of the fourth dimension in recovering the ancient texts of Hippocrates, Galen and others (which much of the medical community was focused around at the time).[36]

Vesalius was the first to publish a treatise, De Humani Corporis Fabrica, that challenged Galen's anatomical teachings, arguing that they are based on observations of other mammals, not human bodies.[37] The volume included a detailed series of explanations and brilliant drawings of the anatomical parts of homo bodies. Vesalius traveled all the mode from Leuven to Padua for permission to dissect victims from the gallows without fright of persecution. His superbly executed drawings are triumphant descriptions of the differences between dogs and humans, but it took a century for Galen'south influence to fade.

Vesalius' piece of work marked a new era in the study of anatomy and its relation to medicine. Under Vesalius, anatomy became an bodily discipline. "His skill in and attention to dissection featured prominently in his publications as well equally his demonstrations, in his research as well as his teaching."[38] In 1540, Vesalius gave a public demonstration of the inaccuracies of Galen'southward anatomical theories, which are nonetheless the orthodoxy of the medical profession. Vesalius now has on display, for comparison purposes, the skeletons of a human alongside that of an ape of which he was able to prove, that in many cases, Galen's observations were indeed correct for the ape, but conduct little relation to man. Clearly what was needed was a new business relationship of human anatomy. While the lecturer explained human anatomy, as revealed by Galen more than than k years earlier, an assistant pointed to the equivalent details on a dissected corpse. At times, the assistant was unable to discover the organ as described, but invariably the corpse rather than Galen was held to be in fault. Vesalius then decided that he volition dissect corpses himself and trust to the evidence of what he found. His approach was highly controversial, but his evident skill led to his appointment as professor of surgery and anatomy at the University of Padua.

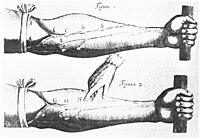

A succession of researchers proceeded to refine the trunk of anatomical knowledge, giving their names to a number of anatomical structures forth the manner. The 16th and 17th centuries also witnessed pregnant advances in the agreement of the circulatory organization, equally the purpose of valves in veins was identified, the left-to-correct ventricle flow of blood through the circulatory organization was described, and the hepatic veins were identified every bit a split up portion of the circulatory organization. The lymphatic system was also identified as a separate organization at this fourth dimension.

Anatomical theatres [edit]

-

A woodcut of an anatomical autopsy, from 1493

-

An anatomical dissection being carried out by Andreas Vesalius, 1543

-

-

-

Sketch of the Preceding painting The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Deijman

-

An Anatomical Theatre In Leiden, 1616

-

The reward of cruelty (Plate Iv) by William Hogarth 1751

In the tardily 16th century, anatomists began exploring and pushing for contention that the report of anatomy could contribute to advancing the boundaries of natural philosophy. However, the bulk of students were more interested in the practicality of beefcake, and less so in the advancement of knowledge of the subject. Students were interested in the technique of autopsy rather than the philosophy of anatomy, and this was reflected in their criticism of Professors such as Girolamo Fabrici.[22]

Anatomical theatres became a popular class for anatomical teaching in the early 16th century. The University of Padua was the kickoff and about widely known theatre, founded in 1594. As a result, Italy became the centre for human dissection. People came from all over to watch as professors taught lectures on the human being physiology and anatomy, equally anyone was welcome to witness the spectacle. Participants "were fascinated by corporeal display, by the torso undergoing autopsy".[39] Well-nigh professors did not do the dissections themselves. Instead, they sat in seats above the bodies while hired hands did the cutting. Students and observers would be placed around the table in a circular, stadium-like loonshit and listen as professors explained the various anatomical parts. As beefcake theatres gained popularity throughout the 16th century, protocols were adjusted to business relationship for the disruptions of students. Students moved beyond simply existence eager to participate, and began stealing and vandalizing cadavers. Students were thus instructed to sit quietly and were to be penalized for disrupting the dissection. Moreover, preparatory lectures were mandatory in gild to introduce the "subsequent ascertainment of anatomy". The demonstrations were structured into dissections and lectures. The dissections focused on the skill of autopsy/vivisection while the lectures would center on the philosophical questions of beefcake. This is exemplary of how anatomy was viewed not only every bit the study of structures simply too the study of the "body equally an extension of the soul".[40] The 19th century eventually saw a move from anatomical theatres to classrooms, reducing "the number of people who could benefit from each cadaver".[half-dozen]

17th century [edit]

Harvey's anatomical researches from De Motu Cordis (1628)

At the beginning of the 17th century, the use of dissecting human cadavers influenced anatomy, leading to a spike in the study of anatomy. The advent of the printing printing facilitated the substitution of ideas. Because the study of anatomy concerned ascertainment and drawings, the popularity of the anatomist was equal to the quality of his drawing talents, and one need not be an expert in Latin to take part.[41] Many famous artists studied anatomy, attended dissections, and published drawings for coin, from Michelangelo to Rembrandt. For the first fourth dimension, prominent universities could teach something nearly anatomy through drawings, rather than relying on knowledge of Latin. Contrary to popular belief, the Church neither objected to nor obstructed anatomical research.[42]

Only certified anatomists were allowed to perform dissections, and sometimes and then only yearly. These dissections were sponsored by the metropolis councilors and ofttimes charged an admission fee, rather like a circus deed for scholars. Many European cities, such every bit Amsterdam, London, Copenhagen, Padua, and Paris, all had Royal anatomists (or some such office) tied to local regime. Indeed, Nicolaes Tulp was Mayor of Amsterdam for iii terms. Though information technology was a risky concern to perform dissections, and unpredictable depending on the availability of fresh bodies, attending dissections was legal.[ citation needed ]

The supply of printed anatomy books from Italy and France led to an increased demand for human cadavers for dissections. Since few bodies were voluntarily donated for dissection, majestic charters were established which allowed prominent universities to use the bodies of hanged criminals for dissections. All the same, at that place was still a shortage of bodies that could not conform for the high demand of bodies.

Modern Anatomy [edit]

18th century [edit]

Until the middle of the 18th century, there was a quota of ten cadavers for each the Royal Higher of Physicians and the Company of Barber Surgeons, the only 2 groups permitted to perform dissections. During the first half of the 18th century, William Cheselden challenged the Visitor of Hairdresser Surgeon'southward exclusive rights on dissections. He was the first to hold regular anatomy lectures and demonstrations. He also wrote The Anatomy of the Humane Body, a student handbook of beefcake.[43] In 1752, the rapid growth of medical schools in England and the pressing need for cadavers led to the passage of the Murder Deed. This allowed medical schools in England to legally dissect bodies of executed murderers for anatomical instruction and research and also aimed to prevent murder. To farther increment the supply of cadavers, the government increased the number of crimes in which hanging was a punishment. Although the number of cadavers increased, it was still non enough to meet the demand of anatomical and medical training.[44]

Since few bodies were voluntarily donated for dissection, criminals that were hanged for murder were dissected. However, there was a shortage of bodies that could not arrange the loftier demand of bodies.[45] To cope with shortages of cadavers and the rise in medical students during the 17th and 18th centuries, body-snatching and fifty-fifty beefcake murder were expert to obtain cadavers.[46] 'Trunk snatching' was the act of sneaking into a graveyard, digging up a corpse and using information technology for study. Men known every bit 'resurrectionists' emerged as outside parties, who would steal corpses for a living and sell the bodies to anatomy schools. The leading London anatomist John Hunter paid for a regular supply of corpses for his beefcake school.[47] During the 17th and 18th centuries, the perception of dissections had evolved into a form of capital punishment. Dissections were considered a dishonor. The corpse was mutilated and not suitable for a funeral. By the terminate of the 18th century, many European countries had passed legislation like to the Murder Act in England to encounter the need of fresh cadavers and to reduce crime. Countries allowed institutions to utilize unclaimed bodies of paupers, prison inmates, and people in psychiatric and charitable hospitals for autopsy.[44] Unfortunately, the lack of bodies available for autopsy and the controversial air that surrounded anatomy in the late 17th century and early 18th century acquired a halt in progress that is evident by the lack of updates made to anatomical texts of the fourth dimension between editions. Additionally, most of the investigations into anatomy were aimed at developing the knowledge of physiology and surgery. Naturally this meant that a close test of the more detailed aspects of beefcake that could advance anatomical knowledge was non a priority.[48]

Paris Medicine was notorious for its influence on medical idea and its contributions to medical knowledge. The new hospital medicine in France during the late 18th century was brought nigh in part past the Law of 1794 which fabricated physicians and surgeons equals in the earth of medical care. The law came every bit a response to the increase need for medical professionals capable of caring for the increase in injuries and diseases brought virtually by French Revolution. The law likewise supplemented schools with bodies for anatomical lessons. Ultimately this created the opportunity for the field of medicine to grow in the direction of "localism of pathological anatomy, the development of advisable diagnostic techniques, and the numerical arroyo to affliction and therapeutics."[ citation needed ]

The British Parliament passed the Beefcake Human action 1832, which finally provided for an adequate and legitimate supply of corpses by allowing legal dissection of executed murderers. The view of anatomist at the time, notwithstanding, became similar to that of an executioner. Having one's torso dissected was seen equally a punishment worse than death, "if you stole a pig, you were hung. If yous killed a man, you were hung and so dissected." Need grew so great that some anatomist resorted to dissecting their ain family unit members as well as robbing bodies from their graves.[49]

Many Europeans interested in the study of beefcake traveled to Italy, then the centre of anatomy. Only in Italy could certain important research methods be used, such as dissections on women. Realdo Colombo (likewise known as Realdus Columbus) and Gabriele Falloppio were pupils of Vesalius. Columbus, every bit Vesalius's immediate successor in Padua, and afterwards professor at Rome, distinguished himself past describing the shape and cavities of the heart, the structure of the pulmonary artery and aorta and their valves, and tracing the course of the blood from the right to the left side of the heart.[50]

The rising in anatomy lead to diverse discoveries and findings. In 1628, English physician William Harvey observed circulating blood through dissections of his male parent's and sister'southward bodies. He published De moto cordis et sanguinis, a treatise in which he explained his theory.[44] In Tuscany and Florence, Marcello Malpighi founded microscopic anatomy, and Nils Steensen studied the anatomy of lymph nodes and salivary glands. By the end of the 17th century, Gaetano Zumbo developed anatomical wax modeling techniques.[51] Antonio Valsalva, a student of Malpighi and a professor of anatomy at University of Bologna, was one of the greatest anatomists of the fourth dimension. He is known by many as the founder of anatomy and physiology of the ear.[52] In the 18th century, Giovanni Batista Morgagni related pre-mortem symptoms with post-mortem pathological findings using pathological anatomy in his book De Sedibus.[53] This led to the rise of morbid anatomy in France and Europe. The rise of morbid anatomy was one of the contributing factors to the shift in power between doctors and physicians, giving ability to the physicians over patients.[54] With the invention of the Stethoscope in 1816, R.T.H. Laennec was able to help bridge the gap between a symptomatic approach to medicine and disease, to one based on anatomy and physiology. His disease and treatments were based on "pathological anatomy" and because this approach to disease was rooted in anatomy instead of symptoms, the process of evaluation and treatment were also forced to evolve.[55] From the belatedly 18th century to the early 19th century, the work of professionals such as Morgagni, Scott Matthew Baillie, and Xavier Bichat served to demonstrate exactly how the detailed anatomical inspection of organs could pb to a more than empirical means of agreement disease and health that would combine medical theory with medical practice. This "pathological anatomy" paved the way for "clinical pathology that practical the noesis of opening up corpses and quantifying illnesses to treatments."[56] Along with the popularity of anatomy and dissection came an increasing interest in the preservation of dissected specimens. In the 17th century, many of the anatomical specimens were stale and stored in cabinets. In kingdom of the netherlands, there were attempts to replicate Egyptian mummies by preserving soft tissue. This became known every bit Balsaming. In the 1660s the Dutch were besides attempting to preserve organs by injecting wax to keep the organ'southward shape. Dyes and mercury were added to the wax to better differentiate and see diverse anatomical structures for academic and research anatomy. By the belatedly 18th century, Thomas Pole published The Anatomic Instructor, which detailed how to dry out and preserve specimens and soft tissue.[57]

19th century anatomy [edit]

During the 19th century, anatomical enquiry was extended with histology and developmental biology of both humans and animals. Women, who were not allowed to attend medical schoolhouse, could attend the anatomy theatres. From 1822 the Regal College of Surgeons forced unregulated schools to close.[58] Medical museums provided examples in comparative beefcake, and were oft used in teaching.[59]

Current Research [edit]

Anatomical enquiry in the past hundred years has taken advantage of technological developments and growing agreement of sciences such as evolutionary and molecular biology to create a thorough understanding of the body's organs and structures. Disciplines such as endocrinology have explained the purpose of glands that anatomists previously could not explain; medical devices such equally MRI machines and CAT scanners have enabled researchers to study organs, living or dead, in unprecedented detail. Progress today in anatomy is centered in the development, evolution, and function of anatomical features, as the macroscopic aspects of human anatomy accept largely been catalogued. Non-human beefcake is particularly active every bit researchers utilize techniques ranging from finite element analysis to molecular biological science.

To save time, some medical schools such as Birmingham, England have adopted prosection, where a demonstrator dissects and explains to an audience, in identify of dissection by students. This enables students to observe more than one torso. Improvements in colour images and photography means that an anatomy text is no longer an aid to dissection but rather a central material to learn from. Plastic anatomical models are regularly used in beefcake pedagogy, offering a good substitute to the real thing. Utilize of living models for anatomy demonstration is over again becoming popular inside instruction of anatomy. Surface landmarks that tin be palpated on another individual provide exercise for future clinical situations. Information technology is possible to do this on oneself; in the Integrated Biological science form at the University of Berkeley, students are encouraged to "introspect"[lx] on themselves and link what they are beingness taught to their own trunk.[58]

Donations of bodies accept declined with public confidence in the medical profession.[61] In U.k., the Homo Tissue Human action 2004 has tightened up the availability of resource to anatomy departments. The outbreaks of bovine spongiform encephalitis (BSE) in the belatedly 1980s and early 1990s farther restricted the handling of encephalon tissue.[58] [62]

The controversy of Gunther von Hagens and public displays of dissections, preserved by plastination, may divide opinions on what is upstanding or legal.[63]

References [edit]

- ^ Lindemann, Mary (2010). Medicine and Club in Early Modern Europe (2d ed.). Cambridge, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland: Cambridge Academy Printing. p. 91.

- ^ Porter, Roy (1999-ten-17). The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity (The Norton History of Science). W. Westward. Norton. pp. 49–fifty. ISBN9780393319804 . Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ Singer, Charles (1957). A Short History of Anatomy & Physiology from Greeks to Harvey. NEw York: Dover Publications Inc. p. 5.

- ^ Singer, Charles (1957). A Short History of Anatomy & Physiology from Greeks to Harvey. NEw York: Dover Publications Inc. p. seven.

- ^ Singer, Charles (1957). A Short History of Anatomy & Physiology from Greeks to Harvey. NEw York: Dover Publications Inc. p. ten.

- ^ a b c Siddiquey, Ak Shamsuddin Husain (2009). "History of Beefcake". Bangladesh Journal of Beefcake. 7 (1): one–3. doi:10.3329/bja.v7i1.3008.

- ^ Vocalizer, Charles (1957). A Short History of Beefcake & Physiology from Greeks to Harvey. NEw York: Dover Publications Inc. p. 29.

- ^ Bay, Noel Si-Yang; Bay, Benefaction-Huat (Dec 2022). "Greek anatomist herophilus: the father of beefcake". Anatomy & Cell Biology. 43 (4): 280–283. doi:ten.5115/acb.2010.43.iv.280. ISSN 2093-3665. PMC3026179. PMID 21267401.

- ^ Nutton, V. (2002). "Logic, Learning, and Experimental Medicine". Science. 295 (5556): 800–801. doi:ten.1126/scientific discipline.1066244. PMID 11823624.

- ^ Hankinson, R. J. (2014). "Partitioning the Soul: Galen on the Anatomy of the Psychic Functions and Mental Affliction". Partitioning the Soul. De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110311884.85. ISBN9783110311884.

- ^ Singer, Charles (1957). A Short History of Anatomy & Physiology from Greeks to Harvey. NEw York: Dover Publications Inc. p. 47.

- ^ Boas, Marie (1970). The Scientific Renaissance 1450-1630. Fontana. pp. 120, 248.

Vesalius, finding Galen total of errors, was quite certain that he had been able to eradicate them.

- ^ Boas, Marie (1970). The Scientific Renaissance 1450-1630. Fontana. p. 262.

Like whatsoever sixteenth-century anatomist also he [Harvey] began with what Gelen had taught and managed to interpret Galen's words to win support for his new doctrine.

- ^ Pasipoularides, Ares (March one, 2022). "Galen, begetter of systematic medicine. An essay on the evolution of modern medicine and cardiology". International Journal of Cardiology. 172 (1): 47–58. doi:ten.1016/j.ijcard.2013.12.166. PMID 24461486.

- ^ Aird, Westward. C. (2011). "Discovery of the cardiovascular system: from Galen to William Harvey". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. ix (s1): 118–129. doi:ten.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04312.x. ISSN 1538-7836. PMID 21781247. S2CID 12092592.

- ^ a b c d Neder, J. Alberto (2020-06-01). "Cardiovascular and pulmonary interactions: why Galen's misconceptions proved clinically useful for one,300 years". Advances in Physiology Education. 44 (ii): 225–231. doi:10.1152/advan.00058.2020. ISSN 1043-4046. PMID 32412380. S2CID 218648041.

- ^ Fleming, Donald (1955). "Galen on the Motions of the Claret in the Heart and Lungs". Isis. 46 (1): fourteen–21. doi:ten.1086/348379. ISSN 0021-1753. JSTOR 226820. PMID 14353581. S2CID 29583656.

- ^ Siraisi, Nancey G. (1990). Medieval and Early Renaissance Medicine . Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. p. 84. ISBN978-0-226-76129-9.

- ^ Park, Katherine (Nov 2022). "Myth 5 - That the Medieval Church Prohibited Dissection". In Numbers, Ronald L. (ed.). Galileo Goes to Jail and Other Myths about Science and Religion. Harvard University Press. pp. 43–49. ISBN9780674057418.

- ^ Nutton, Vivian (2004). Ancient Medicine . London and New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. p. 138. ISBN978-0-415-36848-3.

- ^ Crombie, A.C. (1967). Medieval and Early Mod Scientific discipline (book 1 ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Printing. p. 180 and 181.

- ^ a b Klestinec, Cynthia (2004). "A History of Anatomy Theaters in Sixteenth-Century Padua". Journal of the History of Medicine. 59 (3): 376–379. doi:10.1093/jhmas/59.3.375. PMID 15270335.

- ^ Persaud, Tubbs, Loukas, T.V.Due north, Shane R. Marios (2014). A History of Human Anatomy. Springfield, Illinois: Charles C. Thomas Publisher, LTD. p. 55. ISBN978-0-398-08105-viii.

{{cite volume}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors listing (link) - ^ lindemann, mary (2010). Medicine and Society in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge university press. p. 92. ISBN978-0-521-73256-7.

- ^ Gordon, Benjamin Lee (1959). Medieval and Renaissance Medicine. New York: Philosophical Library, Inc. pp. 422–426.

- ^ Persaud, Loukas, Tubbs, T.V.N. Marios, Shane R. (2014). A History of Human Anatomy (Second ed.). Springfield, Illinois, U.s.A: Charles C. Thomas, Publisher, LTD. pp. 56, 55–59. ISBN978-0-398-08105-8 . Retrieved 2015-11-28 .

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Zimmerman, Leo M.; Veith, Ilza (1993-08-01). Great Ideas in the History of Surgery. Norman Publishing. ISBN9780930405533 . Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- ^ Crombie, Alistair Cameron (1959). The History of Scientific discipline From Augustine to Galileo. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN9780486288505 . Retrieved xix Dec 2022.

- ^ Benivieni, Antonio; Polybus; Guinterius, Joannes (1529). De abditis nonnullis ac mirandis morborum & sanationum causis. apud Andream Cratandrum. Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- ^ Boas, Marie (1970). The Scientific Renaissance 1450–1630. Fontana. pp. 120–143. (Offset published by Collins, 1962)

- ^ Mason, Stephen F. (1962). A History of the Sciences. New York: Collier. p. 550.

- ^ a b c O'Malley, Charles D. (1983). Leonardo on the Human Body. New York: Dover.

- ^ "Leonardo the Man, His machines". Lairweb. Retrieved ii Nov 2022.

- ^ "Leonardo Da Vinci start Anatomist". Life in The Fast Lane. 2009-04-19. Retrieved two November 2022.

- ^ "Leonardo Da Vinci's Notebook Project". Irvine Valley College. Archived from the original on 12 Nov 2022. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ KLESTINEC, CYNTHIA (2004). "A History of Anatomy Theaters in Sixteenth-Century Padua". Journal of the History of Medicine. 59 (3): 377. doi:x.1093/jhmas/jrh089. PMID 15270335.

- ^ "Andreas Vesalius | Anatomy in the Age of Enlightenment". www.umich.edu . Retrieved 2017-02-05 .

- ^ Klestinec, Cynthia (2004). "A History of Anatomy Theaters in Sixteenth-Century Padua". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 59 (3): 375–412. doi:10.1093/jhmas/59.3.375. PMID 15270335.

- ^ Klestinec, Cynthia (2004). "A History of Anatomy Theaters in Sixteenth-Century Padua". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 59 (iii): 375–412. doi:10.1093/jhmas/59.3.375. PMID 15270335.

- ^ Klestinec, Cynthia (2004). "A History of Anatomy Theaters in Sixteenth-Century Padua". Journal of the History of Medicine. 59 (iii): 391–392. doi:x.1093/jhmas/59.iii.375. PMID 15270335.

- ^ "Dream Beefcake: Exhibition Information". NLM.

- ^ Howse, Christopher (x June 2009). "The myth of the anatomy lesson". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ Sanders, Thousand. A. (1999-11-01). "William Cheselden: anatomist, surgeon, and medical illustrator". Spine. 24 (21): 2282–2289. doi:10.1097/00007632-199911010-00019. ISSN 0362-2436. PMID 10562998.

- ^ a b c Ghosh, Sanjib Kumar (2017-03-02). "Human cadaveric dissection: a historical account from aboriginal Hellenic republic to the modernistic era". Anatomy & Cell Biology. 48 (3): 153–169. doi:ten.5115/acb.2015.48.three.153. PMC4582158. PMID 26417475.

- ^ Mitchell, Piers D; Boston, Ceridwen; Chamberlain, Andrew T; Chaplin, Simon; Chauhan, Vin; Evans, Jonathan; Fowler, Louise; Powers, Natasha; Walker, Don (2017-02-17). "The written report of beefcake in England from 1700 to the early 20th century". Journal of Anatomy. 219 (2): 91–99. doi:ten.1111/j.1469-7580.2011.01381.10. ISSN 0021-8782. PMC3162231. PMID 21496014.

- ^ Rosner, Lisa. 2022. The Anatomy Murders. Existence the True and Spectacular History of Edinburgh's Notorious Burke and Hare and of the Man of Science Who Abetted Them in the Commission of Their Most Heinous Crimes. University of Pennsylvania Press

- ^ Moore, Wendy (2006). The Pocketknife Human: Blood, Body-Snatching and the Birth of Modern Surgery. Bantam. pp. 87–95 and passim. ISBN978-0-553-81618-1.

- ^ bynum, west.f (1994). science and the practice of medicine in the nineteenth century. cambridge academy press. p. 12. ISBN978-0-521-27205-6.

- ^ Roach, Mary (2003). Stiff: The curious Lives of Man Cadavers . New York: Due west.W. Norton. pp. 37–57. ISBN9780393050936.

- ^ Boas, Marie (1970). The Scientific Renaissance 1450-1630. Fontana. pp. 254–256.

- ^ Orlandini, Giovanni East.; Paternostro, Ferdinando (2010). "Anatomy and anatomists in Tuscany in the 17th century". Italian Journal of Beefcake and Embryology = Archivio Italiano di Anatomia ed Embriologia. 115 (3): 167–174. PMID 21287970.

- ^ Wells, Walter A. (1948-02-01). "Antonio valsalva — pioneer in applied anatomy — 1666–1723". The Laryngoscope. 58 (ii): 105–117. doi:10.1002/lary.5540580202. PMID 18904602. S2CID 70524656.

- ^ van den Tweel, Jan G.; Taylor, Clive R. (2017-03-02). "A brief history of pathology". Virchows Archiv. 457 (i): 3–10. doi:10.1007/s00428-010-0934-4. PMC2895866. PMID 20499087.

- ^ Harley, David (1994-04-01). "Political Post-mortems and Morbid Anatomy in Seventeenth-century England". Social History of Medicine. 7 (ane): 1–28. doi:10.1093/shm/vii.ane.ane. PMID 11639292.

- ^ bynum, westward.f (1994). scientific discipline and the practice of medicine in the nineteenth century. Cambridge Academy Printing. p. 41. ISBN978-0-521-27205-6.

- ^ lindemann, mary (2010). medicine and gild in early modernistic Europe. cambridge academy press. pp. 111–112. ISBN978-0-521-73256-7.

- ^ Mitchell, Piers D; Boston, Ceridwen; Chamberlain, Andrew T; Chaplin, Simon; Chauhan, Vin; Evans, Jonathan; Fowler, Louise; Powers, Natasha; Walker, Don (2017-03-02). "The study of anatomy in England from 1700 to the early 20th century". Periodical of Beefcake. 219 (2): 91–99. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2011.01381.x. PMC3162231. PMID 21496014.

- ^ a b c McLachlan J.; Patten D. (2006). "Beefcake teaching: ghosts of the past, present and future". Medical Instruction. 40 (3): 243–53. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02401.ten. PMID 16483327. S2CID 30909540.

- ^ Reinarz J (2005). "The age of museum medicine: The rise and fall of the medical museum at Birmingham'south School of Medicine". Social History of Medicine. 18 (3): 419–37. doi:x.1093/shm/hki050.

- ^ Diamond M. 2005. Integrative Biology 131 - Lecture 01: Organisation of Body. Berkeley, University of California.

- ^ British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) News. 2001. Organ scandal groundwork. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/howdy/health/1136723.stm Accessed 22 April 2008.

- ^ Demiryurek D.; Bayramoglu A; Ustacelebi Due south. (2002). "Infective agents in fixed human cadavers: a brief review and suggested guidelines". Anatomical Tape. 269 (1): 194–7. doi:10.1002/ar.10143. PMID 12209557. S2CID 20948827.

- ^ British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) News. 2002 Controversial autopsy goes ahead. http://news.bbc.co.united kingdom/i/hullo/health/2493291.stm Accessed 22 April 2008.

Bibliography [edit]

- Knoeff, Rina (2012). Dutch Beefcake and Clinical Medicine in 17th-Century Europe. Leibniz Institute of European History.

- Mazzio, C. (1997). The Body in Parts: Discourses and Anatomies in Early Mod Europe. Routledge. ISBN978-0-415-91694-three.

- Porter, R. (1997). The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity from Antiquity to the Present. Harper Collins. ISBN978-0-00-215173-three.

- Sawday, J. (1996). The Body Emblazoned: Dissection and the Human Body in Renaissance Culture. Routledge. ISBN978-0-415-15719-iii.

External links [edit]

- Historical Anatomies on the Web. National Library of Medicine. Selected images from notable anatomical atlases.

- Anatomia 1522-1867: Anatomical Plates from the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library

- Human Anatomy & Physiology Lodge A society to promote communication among teachers of man anatomy and physiology in colleges, universities, and related institutions.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_anatomy

Posted by: buchananlatepred.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Which Period Resulted In The Production Of Realistic Anatomical Drawings?"

Post a Comment